Doc Hellemans on Max Heart Rate Testing

The "220-Age" Formula

David is an experienced 68-year-old runner. On the advice of his running buddies, he finally capitulated and invested in a heart rate monitor. A week later, he came to see me in a panic, announcing that there was something wrong with his heart. His daughter, a fitness instructor, calculated his maximum heart rate with the still widely used ‘MHR=220-age’ formula. At 68 years of age, that made his MHR 152.

Based on that information, she told him to keep his heart rate around 115 for steady runs and his harder runs under 145. However, Dave had difficulty keeping his heart rate in the recommended zones. While it felt ‘steady’, his heart rate was 140, and when he encountered a hill, it shot up to 160 without trying too hard.

I asked him how he felt during the run. He answered, ‘I felt fine, but now I am not so sure about that anymore, and I am reluctant to resume training.’

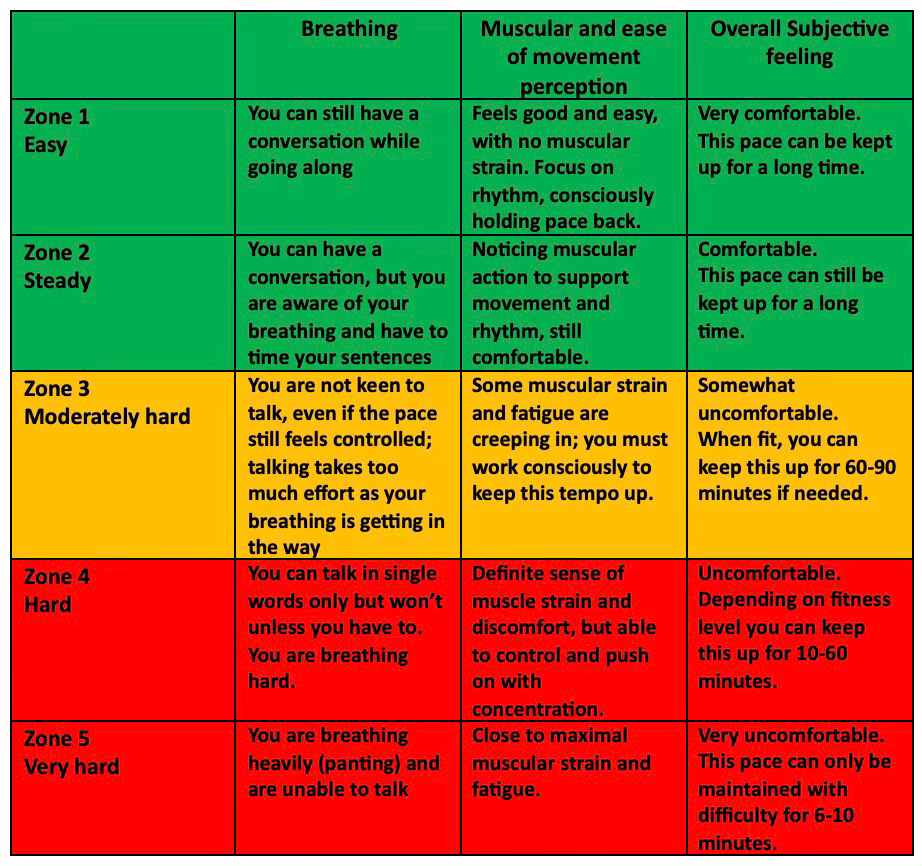

I listened to his heart, which sounded regular, with a resting rate of 64. His blood pressure was normal. He appeared in good health and was on no medication. I put him on a treadmill and gradually ramped up his speed every three minutes, asking him repeatedly to score his perceived effort on a score of 1-5 (1=easy, 2=steady, 3=mod hard, 4=hard and 5=very hard) while monitoring his heart rate.

His heart rate quickly increased and was 140 in what he perceived as his steady zone (Zone 2). He looked comfortable.

When I ramped up the speed to his calculated MHR of 152, he scored 2.5-3. He still looked comfortable.

I increased the treadmill's speed a bit more, and his heart rate shot up to 170, while he scored 3.5-4, which is moderately hard to hard.

I let him sit there for a bit, and his heart rate drifted up to 176 after a couple of minutes. He nodded when I asked if he could go a bit faster.

I wound the treadmill up another notch and told him he could stop when he felt close to maximum effort. His heart rate increased to 182 before he pushed the treadmill's red ‘stop’ button.

After this workout, his heart rate returned to below 120 within one minute, suggesting excellent aerobic fitness. His heart rate had been regular all the way through the test. I reassured him and sent him home with his new heart rate zones based on the combination of his subjective score and his heart rate response during the test, as well as the following explanation:

The ‘MHR=220-age’ formula was introduced by Dr William Haskell and Dr Samuel Fox in 1970 when heart rate monitoring was gaining traction. This formula was not developed from original research but resulted from observation based on data from approximately 11 references of published or unpublished scientific compilations. It pointed merely to the average decline in heart rate for a large study population.

However, the formula soon found traction in the fitness industry because of its simplicity (who can’t subtract their age from 220….). Even reputable organisations like the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the American Heart Association have promoted its use for many years. Polar Electro, the first company to popularise heart rate monitors, popularised the formula worldwide by including it in their guidelines.

Dr Haskell, one of the formula's creators, has since remarked about its widespread use, stating it was never intended to be a rigid training rule for individual patients and athletes. He confirmed that the formula applies to the average maximum heart rate of a large group of people and does not apply to the individual as there is significant variety in individual MHR. Dave is a good example, with a calculated MHR of 152 but a true MHR of 182+.

We know that our MHR reduces with ageing due to a combination of weakening of the heart muscle, an increase in resistance of the peripheral blood vessels and a reduced ability to respond to signals from the nervous system. While the exact rate of decline can vary among individuals, a commonly cited estimate is that our maximum heart rate decreases by approximately one beat per minute per year from age 30. This means that a person's maximum heart rate at 40 might be about ten beats per minute lower than it was at 30, and so on. However, this decline in MHR can be influenced by factors such as fitness level, genetics, and overall health. Regular exercise, especially aerobic exercise, can play a significant role in maintaining cardiovascular health and potentially slowing the decrease in maximum heart rate associated with ageing.

To get an accurate reading of your maximum heart rate, run or bike up a hill for 4-6 minutes in zones 4-5, and when you feel you can’t go on much longer, put in an extra effort (sprint). Look at your heart rate monitor before you keel over; that is your maximum heart rate.

The 6-minute test, as described in previous articles in Endurance Essentials, is also a good measure of getting close to your MHR.

To do a proper maximum heart rate test, you must be healthy and have some basic fitness. If you are over the age of 35 and new to exercise, we recommend that you get a doctor's clearance first. The alternative is to have a submaximal test with a fitness professional, as they can extrapolate an estimation of your MHR from the feedback they get from the test.

Back to Table of Contents