Consider writing out a Strength Inventory by asking yourself a series of questions:

Strong for what?

Strong when?

How do I stack up relative to my peers?

What are my future goals?

Are there strength limitations preventing me from reaching my training potential?

Do I have sufficient muscle mass to see me through to the end of my athletic career?

What is my strength reserve for everyday living?

Do I have the ability to absorb impacts inherent in my sport? Bone strength, connective tissue strength and overall resilience to impact.

The answers to these questions will help us navigate the conflicting advice on “strength training.”

Defining Terms

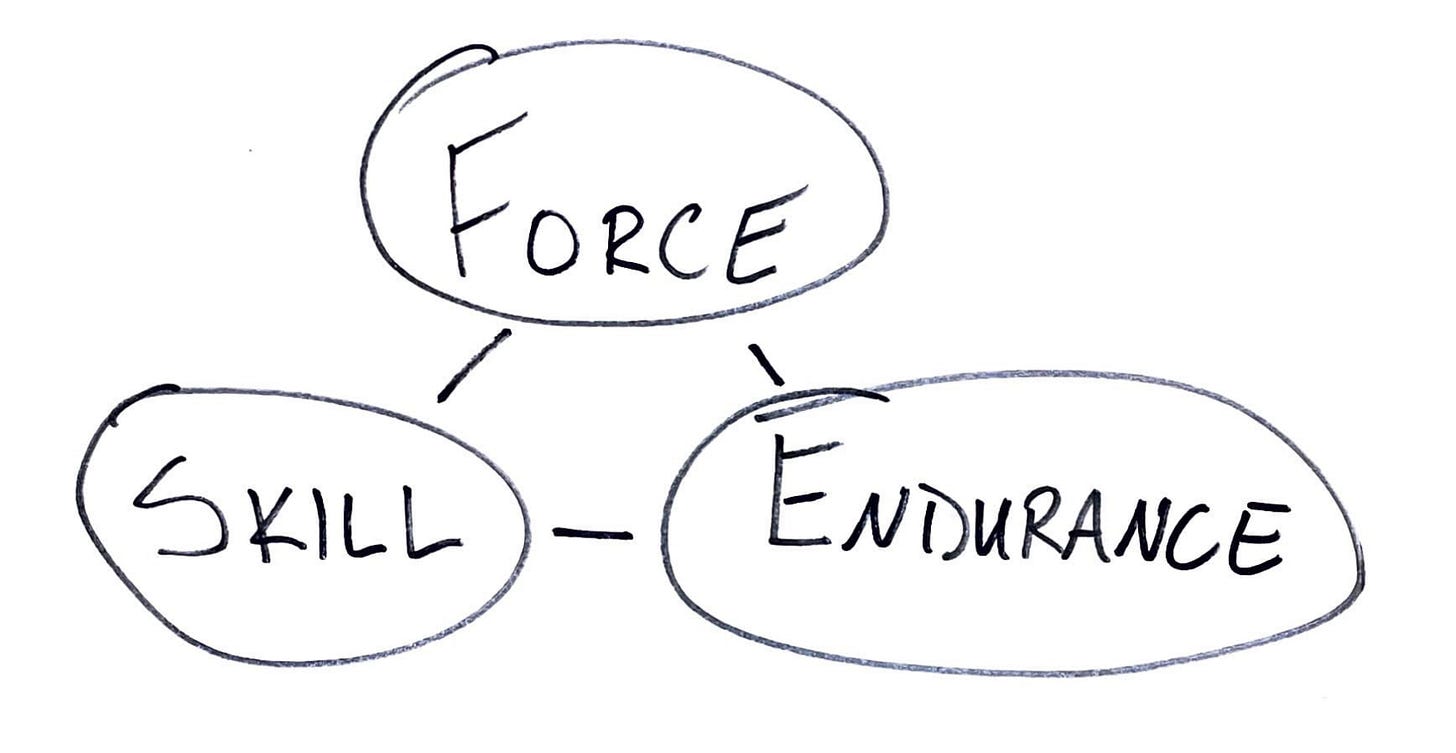

FORCE is a vector, it has both magnitude and direction.

SKILL is the ability to direct the vector and create velocity.

ENDURANCE is the ability to sustain work over time.

This framework is useful to guide overall training.

It’s also helpful to direct strength training.

For an athlete, “strong” is specific to the context of their sport and an apparent “lack of strength” might not be caused by an inability to generate force.

Toss a body builder in the water and you’ll see a lack of skill. Plenty of force, limited velocity, and little endurance.

Take any novice runner beyond their durability limits and you’ll see a lack of endurance.

It is for this reason, that many coaches (such as my writing partner, John Hellemans) prefer an in-sport approach to strength.

An in-sport approach has many advantages - the most important being the ability to improve Force-Skill-Endurance simultaneously in a way that supports race performance.

But athletics is about more than our current season.

There is another component of performance.

TIME.

Not the endurance required for a race or season. Rather, the ability to generate force across an athlete’s lifespan. The ability to generate force 10, 20 & 30 years from now. Strong at 35 is not the same as strong at 55, or 75.

The capacity to stay-in-the-game is a big part of our Endurance Journey. Traditional strength training has a role in keeping us in the game. Much of an endurance athlete’s program is catabolic in nature, breaking us down. Taking time to build our bodies up is important.

In addition to time, aerobic fitness has a volumetric component. More muscle volume, means more aerobic potential.

For young athletes, stunted muscular development can hinder athletic careers.

Female athletes, who miss their window to develop sport specific strength, can struggle to compete. This is particularly relevant for sports requiring upper body force production.

As endurance training gradually changes body composition, muscular athletes can have outstanding endurance careers.

Recap

Let’s come back to the questions we started with…

Strong for what?

Strong for the specific demands of our sport

Strong for everyday living.

Strong when?

Strong for the demands of our A-race

Strong for our entire lives.

There is a balance between near and far.

Strength training has a role to play in the maintenance of our long term health.