In this article I am going to cover:

Conventional Altitude Training (live high, train high)

Which Altitude To Choose

How To Train

Using Lactate

What To Monitor

What To Expect Post-Altitude

Introduction

In previous articles, we covered the science behind altitude training. We learned how oxygen finds its way from the atmosphere to the energy-producing mitochondria within the muscle cells and how a reduced amount of oxygen in the outside air reduces oxygen availability for the mitochondria. As oxygen is essential for survival, the body kicks into action when exposed to a hypoxic (low oxygen) environment, with acute and chronic adaptations to make the oxygen pathway more efficient. Much emphasis has been placed on the red blood cell response to hypoxia in the literature. Still, additional adaptations, particularly downstream, where oxygen enters the muscle cells and is processed in the mitochondria, are just as important. In this article, we will explore how science translates into practice.

Conventional Altitude Training

There are two main altitude training methods: natural altitude training and altitude simulation. The latter creates a hypoxic environment with artificial devices. This includes the use of hypoxicators, altitude tents and houses. Altitude simulation methods will be discussed in a later article.

Natural altitude training methods include conventional altitude training (live high-train high) and alternative methods, combining different altitudes for living and training. Of these, the live high-train low method has become more popular as science has indicated that this is potentially the more effective form of altitude training. However, the conventional live high-train high is still the most commonly practised form of altitude training. The likely reason for this is that the live high-train low method comes with significant logistical (travel) issues. I will discuss alternative natural training methods in the next article.

Conventional altitude training consists of living and training for periods of time at an altitude between 1000 and 2500 meters (1000 to 8000 feet). The risk that the training process is compromised increases with higher altitudes, hence the general recommendation to stay below 2500 meters. Acute adaptations (increase in ventilation and heart rate) occur in the first three days after arrival, after which the more chronic adaptations kick in (see previous article). After two weeks, you will feel well acclimatised, but adaptations continue after that at a reduced rate. Two weeks is considered the minimum time to go to altitude; three to four weeks is more common. Some athletes choose to live at altitude for large parts of the year. We are all aware of the Kenyans who grow up and live and train at altitude during their developing years, which is thought to give them a distinct advantage over their mainly sea-level-based opponents. The more you have been exposed to altitude, the quicker you (re)acclimatise and better cope with the hypoxic environment. The result is that over time, through repeated exposure, your ability to train will be similar to sea level, increasing its effectiveness. Don’t give up if your first experience does not benefit you or even has an adverse effect.

The Best Altitude To Choose

In my experience, for most athletes, it is best to stay under 2000 meters (6500 feet) when they go to altitude for the first time, so they can get a taste and check their response. The athletes need to be able to maintain some quality of training; otherwise, the altitude camp will be counterproductive. There are many places in the world between 1600 and 2000 meters above sea level where you get a strong response from exposure to altitude combined with the ability to still train at a decent level. The more altitude-savvy and experienced athletes can go higher to maximise benefits further, but there is always that risk of illness or compromised training.

When To Go and For How Long

The safest time to go, especially for the first-timer, is pre-season, with an emphasis on aerobic training. The only requirement is good health and some basic fitness. I recommend a minimum time of two weeks, but three is better. Returning from a pre-season altitude camp, when training has been controlled and the mood relaxed, most athletes feel fantastic and ready to get stuck into more specific race-pace training. This can easily backfire if the basic training principles are not adhered to. Feeling good is often the trigger to do ‘too much, too fast, too soon’, so the higher intensity training sessions must be gradually introduced and progressed, leading into the season's first races. Often athletes return to altitude when there is a break in the race calendar to get another boost. This cyclical exposure to altitude can be very effective if managed well and can result in race performance improvements from 1-3%. Some athletes live at altitude for long periods and only come down for short spells to race. As long as they can train and recover similarly compared to sea level, this strategy likely gives them an ongoing advantage.

Training At Altitude

How you execute your training at altitude is as important as exposure to the ‘thin’ air. Many athletes underestimate this principle and step up their training too quickly for fear of losing fitness. You can recover from overreaching at sea level with a couple of easy days. You do not have that luxury at altitude, as the hypoxic environment interferes with recovery.

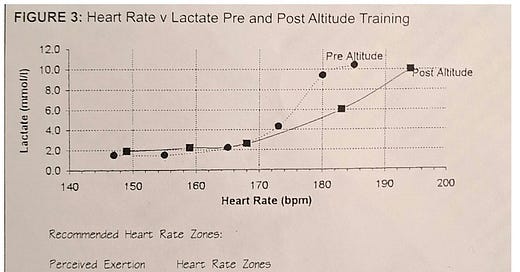

Initially, training at altitude is compromised because of the reduced oxygen availability in the air compared to sea level, and our bodies have not adjusted yet to the new environment. The hypoxic environment adds to the training stress, the extent of which differs between individual athletes. Our heart rate and ventilation increase immediately to compensate for the lower oxygen availability. Additional adaptations to improve oxygen processing gradually kick in in the first week.

Table 1 outlines the recommended changes for training at altitude compared to sea level. Remember that this is a generic example and that variations of this theme will apply to individual athletes. Ongoing monitoring will decide the details of the training planned for every day.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Endurance Essentials to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.