Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) is a complex but increasingly recognised condition among endurance athletes. Having listened to Trent Stellingwerf’s podcast interview (linked below), where he provides a thorough overview of the science behind eating disorders.

I’ve also studied the updated IOC guidelines on RED-S, see HERE and HERE. The figures in this article are from the 2023 IOC Consensus Statement.

Drawing from my experience as a sports medicine doctor (former) and an endurance coach, I have treated and coached numerous athletes with this condition. Here are my observations regarding RED-S:

Prevalence of Eating Disorders: Eating disorders are notably prevalent in elite female endurance athletes. New Zealand-based research indicates that over half of active exercising females are at risk of “low energy availability” (LEA). This aligns with international research and my own experience across my medical and coaching careers.

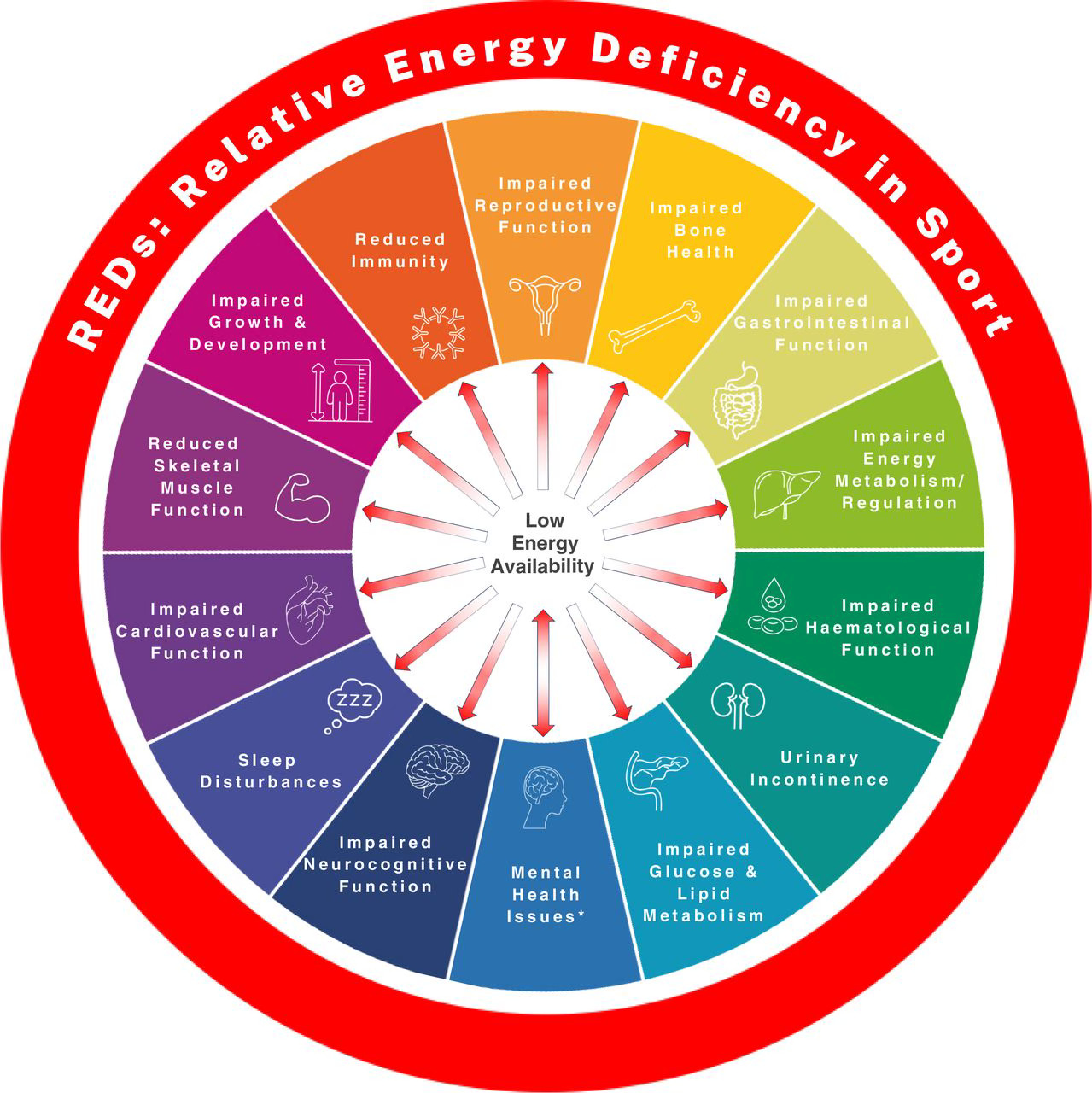

Common Symptoms: Symptoms often include low energy, amenorrhea (absence of periods), low bone density, compromised immune function, gastrointestinal issues, and signs of anxiety or depression. In females, amenorrhea and low blood levels of female hormones are reliable indicators of RED-S; in males, low body weight with reduced testosterone levels is more indicative.

Body Weight Monitoring: Monitoring weight alone is a crude measure of energy balance. Weight may remain stable despite an energy deficit, as the body conserves energy by slowing the basal metabolic rate (BMR), the energy used at rest. When BMR drops below a threshold, essential bodily functions, including hormone production, can become compromised.

Impact on Male Athletes: Although eating disorders appear less prevalent in male athletes, they are still affected, particularly in endurance sports where body composition significantly impacts performance.

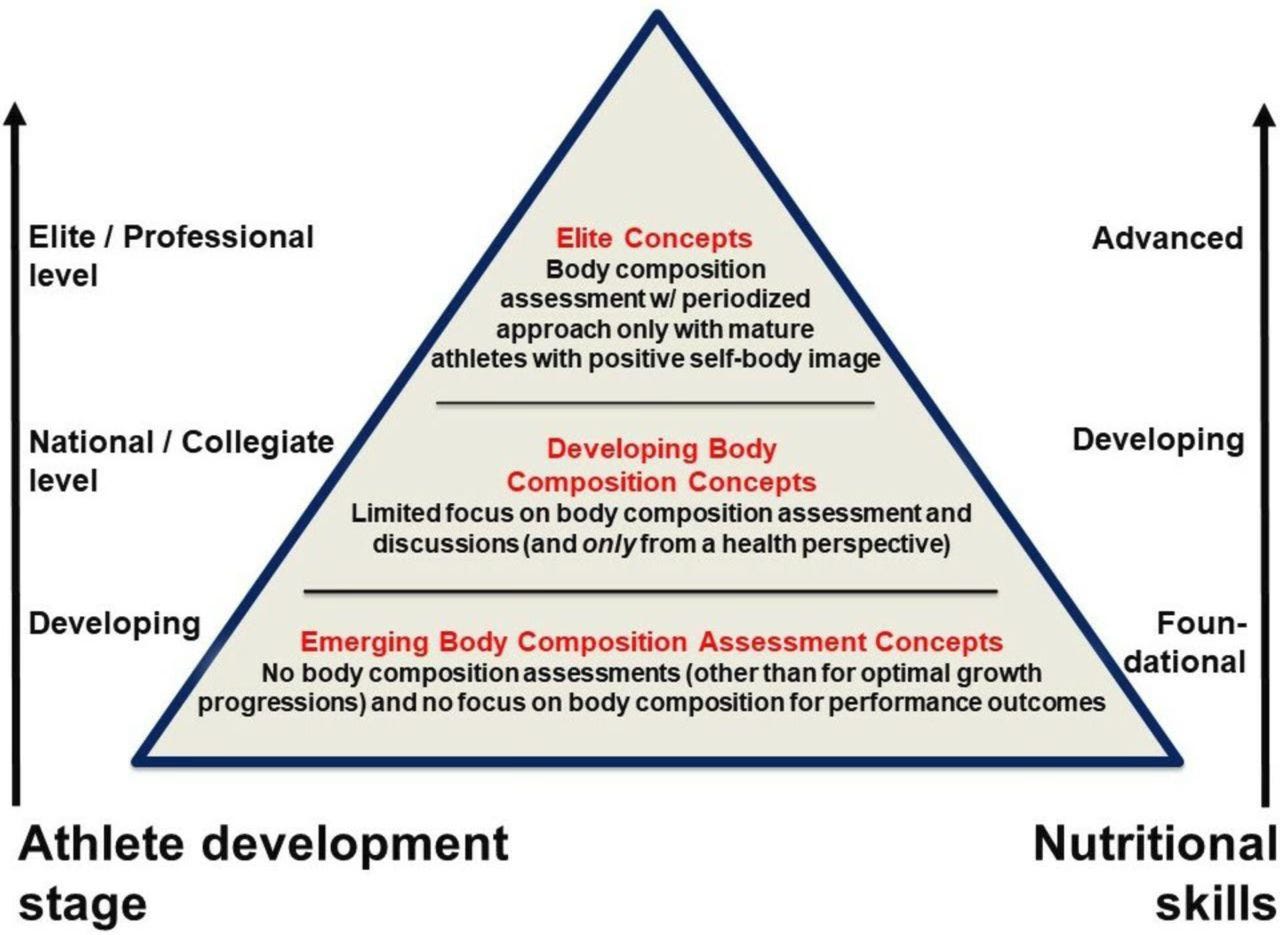

Body Composition and Performance: There is a strong correlation between body composition and performance in sports like running, cycling, and triathlon. For female athletes, amenorrhea and low weight may correlate with peak performance. The power-to-weight ratio is often more critical than weight alone.

Challenges of Finding Optimal Race Weight: Finding and maintaining an optimal race weight is challenging, particularly during an athlete’s developmental years. This requires a balance where the power-to-weight ratio is optimised without sacrificing health.

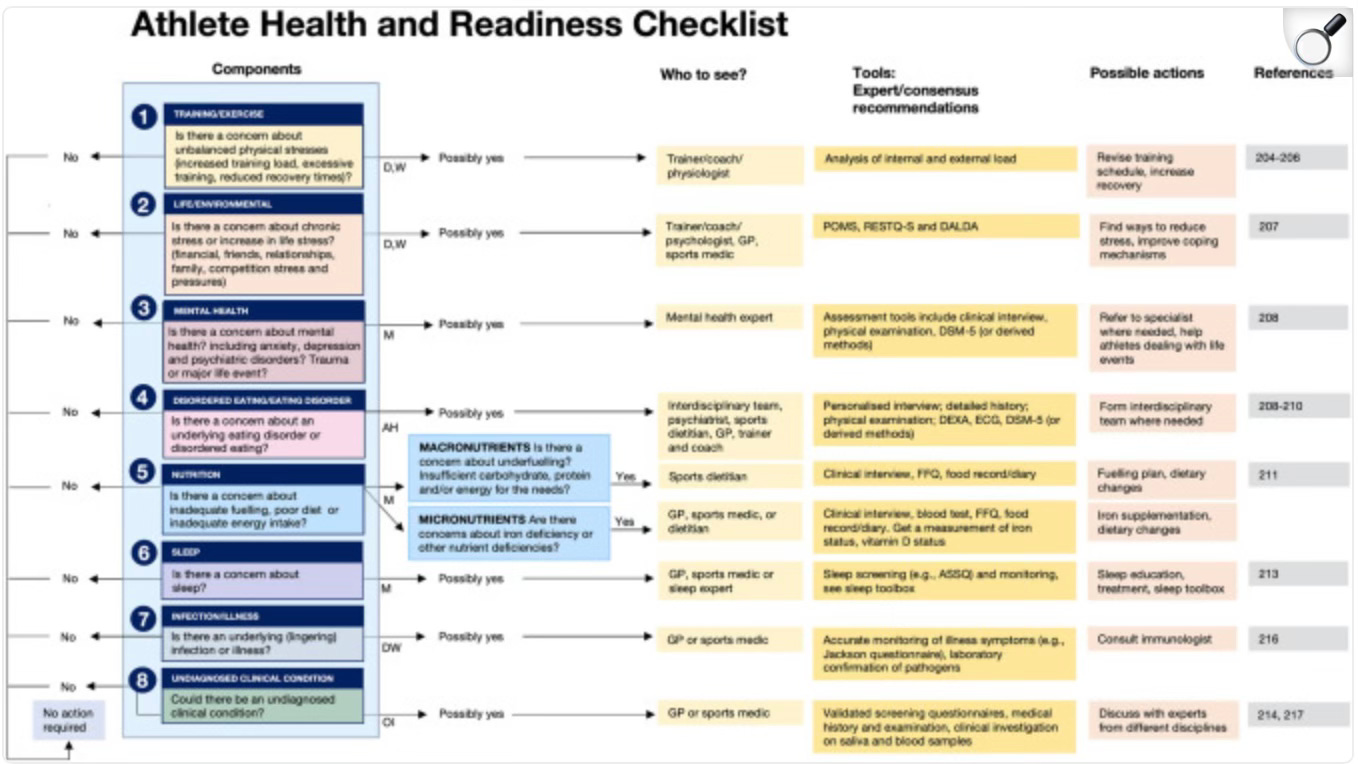

Collaborative Management: Managing eating disorders often requires a multidisciplinary approach involving sports psychologists, dietitians, coaches, sports medicine practitioners, endocrinologists, and, at times, family support. Coaches play an important role in monitoring, but they need support from specialised professionals.

Amenorrhea and Bone Density in Elite Athletes: During international careers, it’s not unusual for female endurance athletes to experience periods of amenorrhea or low-normal bone density, which may not hinder their performance.

Management and Athlete Responsibility: Eating disorders can often be managed effectively, especially when athletes take responsibility for their health. Support from health professionals, including psychologists, dietitians, and sports medicine doctors, can be essential initially.

Encouraging Health-Conscious Behaviour: The potential inability to train or compete can motivate athletes to improve their eating habits. Those who cannot take responsibility for their health often find that the disorder hampers their progress and results.

Intensity of Elite-Level Sports: Competing at an elite level requires commitment, often pushing the body to extremes. Like mountaineers who put their bodies under excessive strain to summit peaks, elite athletes may do the same, with the understanding that recovery is possible afterwards.

Psychological Traits in Elite Sports: Elite athletes often exhibit personality traits such as high discipline, sometimes bordering on obsessive or neurotic tendencies, and are prone to anxiety or depression. These traits may contribute to their ability to maintain the discipline of structured training over many hours a day that is required to get to the very top.

Interest in Nutrition: Most endurance athletes are highly aware of nutrition. Education on achieving an optimal but healthy weight is crucial, particularly when adjusting for the competitive season.

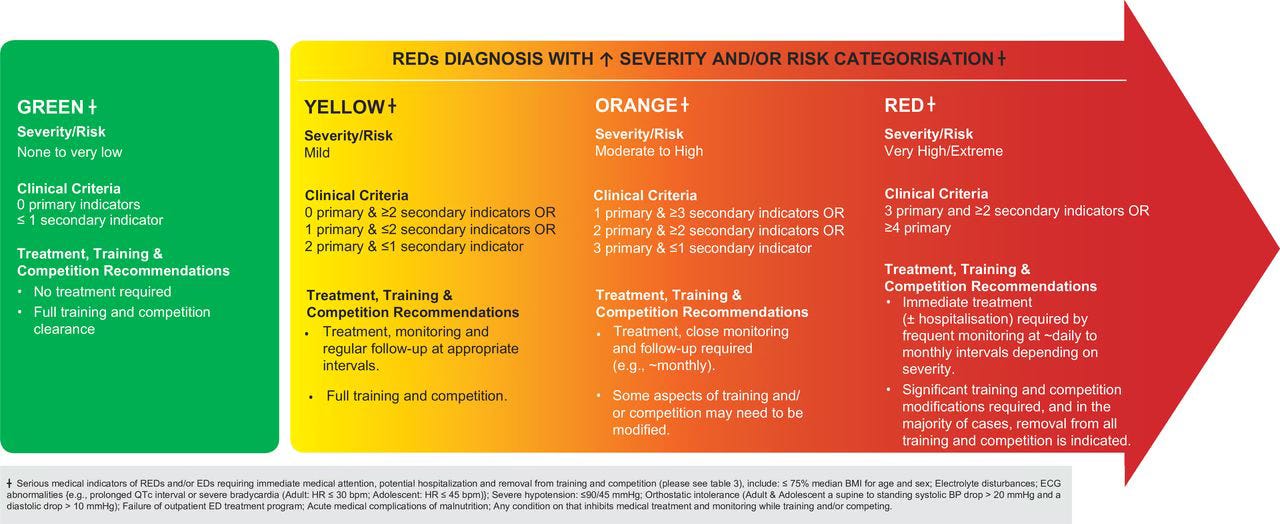

IOC Guidelines and Clinical Judgement: Though useful, the IOC RED-S and Female Athlete Triad assessment tools should be applied with clinical judgement rather than as checklists. For example, the RED-S CAT2 Version 2 tool comes with an essential disclaimer that emphasises its role as an assessment aid, not a substitute for professional diagnosis or treatment. This disclaimer also highlights that approaches can differ significantly between elite and recreational athletes.

Diet’s Role: Diet generally significantly impacts RED-S more than exercise alone. Athletes unsure about their energy intake are best supported by dietitians with experience in sports nutrition, who can assist with meal planning and nutrient timing.

Role of Clinical Psychology: Athletes dealing with eating-related fears may benefit from working with a clinical psychologist, especially when such fears impact their health or performance.

Challenges of Weight Maintenance in High-Volume Training: Elite endurance athletes training 20-30 hours per week may find it challenging to gain weight, especially on a balanced and varied diet. Over time, many of these athletes’ bodies adjust, finding an optimal weight naturally.

Additional Resources

Our Chapter on Body Performance & Nutrition and its Audio Version

Our Article on Top Amateur Nutrition

Link to Article Does REDs Syndrome Exist - an interesting read, particularly the difficulty in distinguishing between adaptive and maladaptive low energy availability. The authors propose an Athlete Health & Readiness Checklist.

Back to Table of Contents