Here’s the link to Part One.

In Part Two we will cover:

Why we experience difficulty managing our weight when training load is high. Shouldn’t high outputs lead to weight loss?

The role of stress and energy availability in long-term body composition and performance.

The role of anxiety in body composition and performance.

Using stability as a high-performance metric.

Manipulating our set points.

High return training strategies.

These thoughts are a mixture of what you’ll read in the book and my own experience.

The book contains more themes than what I touch on in this series.

Output, Stress & Fat Loss

The book takes a balanced look at all the most popular nutrition strategies. You can find our best advice in our Nutrition Chapter.

When seeking to apply anyone’s advice on nutrition, consider the importance of stress management.

Stress management is the first step for weight management

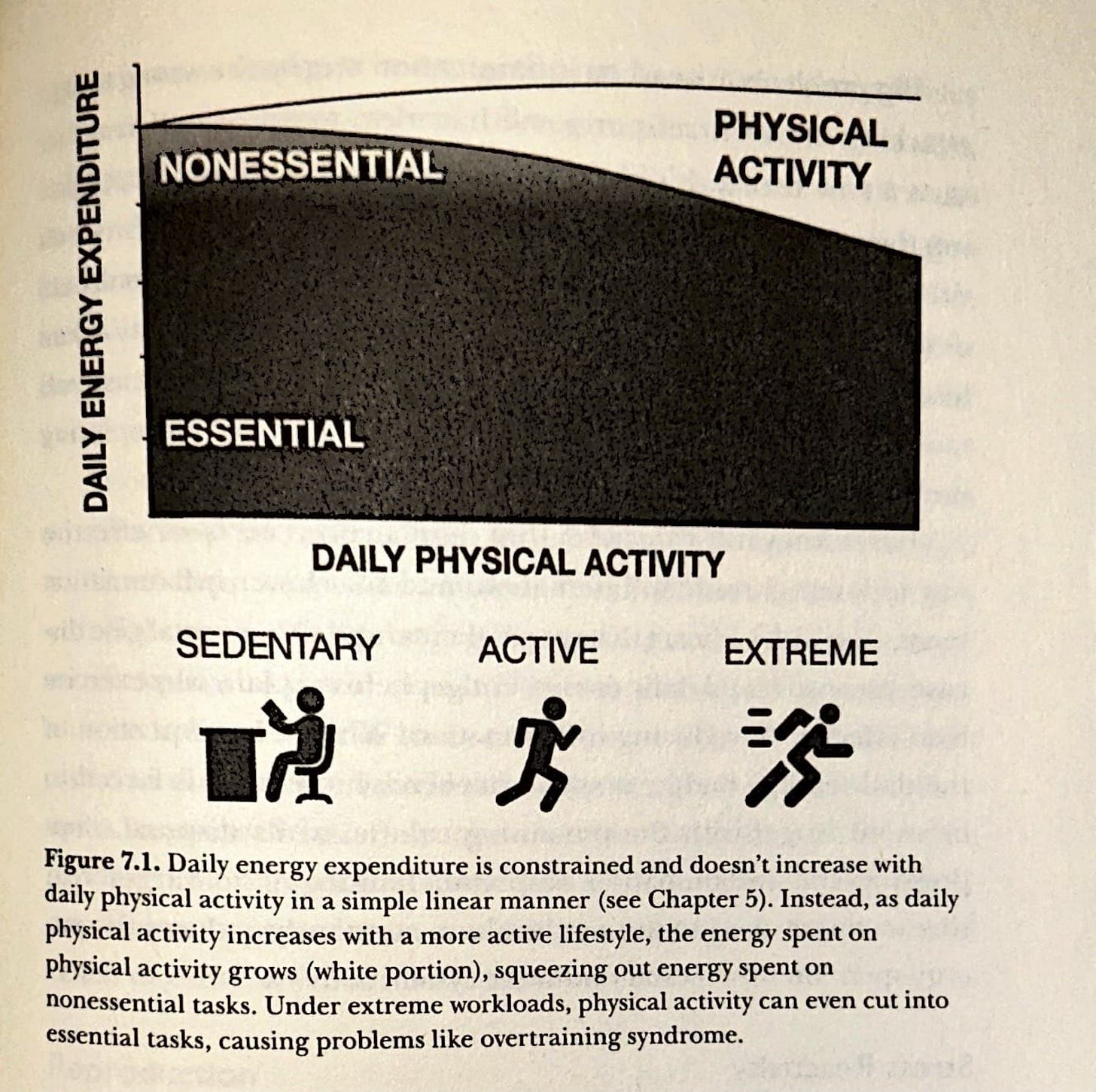

One of the central themes of the book is daily energy expenditure is constrained.

In seeking to apply the ideas contained in the book, I would reframe to: daily stress tolerance is constrained and our first task is to get ourselves to a healthy, stable baseline.

From that point, we can make small, low-stress changes and self-direct our lives.

Aerobic Improvements

Increases in Lean Body Mass

Decreases in Fat Mass

These are achieved by starting at a healthy, stable baseline.

My experience is “pick one.” If you have a desire to achieve everything (lean, strong and fit) then your best bet is seasonal periodization from a healthy baseline.

Low Energy Availability

Well before we’re sick, over-reached or overtrained… we will be underperforming relative to our potential.

Here again, I’d encourage you to focus on stress, rather than energy expenditure. I’ve coached low-output athletes with the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome. They were caught in a cycle of restricting food intake => trying to boost output => with a desire to lose weight. If that sounds like you then the best thing you can do is get to a strong, healthy baseline.

There’s a section of the book that deals with long term impacts of extended periods of low energy availability. Sobering stuff, as some of the people who constrained their input reduced their long term energy set point. “Starvation mode” or “screwing up our metabolism” is how we describe the outcome in common usage. As lifelong athletes, we want to avoid this risk. If that sounds like you then you’re going to need support on both the mental and physical health side. Start by speaking to a doctor with experience helping endurance athletes.

Anxiety Management

Anxiety management flows naturally from accepting that stress tolerance is constrained.

In Part Three of my series on Overtraining & Adrenal Burnout, Clas shares that curing his physical symptoms required peace in his mind.

If you train with highly-anxious friends then you’ve likely witnessed a “stress bonk” where mental anxiety causes a physical shutdown.

The book talks about the hypothalamus down-regulating bodily tasks. Just as high energy expenditure can stress the body, so does an over-active mind.

Once again, making progress on our mental fitness is best done from a healthy, stable baseline. This often requires stepping away from the habits, and goals, that create anxiety in our lives.

This “stepping away” can require a break from racing.

Manipulating Our Set Points

Whether the limit is total stress burden, daily energy expenditure or some other metric… I don’t think it matters.

What matters is awareness of our individual constraints.

Underperformance results from excessive stress. If we exceed our limits for an extended period of time then we will down-regulate essential functions and impair our health.

As athletes, what can we do to boost our set points?

Consider training that yields the greatest return for the lowest overall stress burden.

Green Zone Endurance Training1

Sprints / Strength Training / Plyometrics2

Skills Training

Outdoor Movement - avoiding long periods of sitting

Adequate Real Food Nutrition

Natural Light3

Adequate Sleep

Human Connection

A Sense of Purpose

None of the above require counting, measuring or data.

We are able to feel the choices that build us up.

Body Mass: I don’t see the correlation as clearly as the author… but if it holds then boosting lean body mass will increase our set point. When fast recovery matters, get a little heavy.

When We Go Big

For athletic performance there are times when we will choose to deviate from the choices that build us up. Hopefully, we are healthy (with a high set point) when we make this choice.

Here are tips to keep in mind:

High-performance is a place we visit.

Stressful days need to be spaced.

Stressful blocks need to be recovered from.

Recovery is most beneficial when taken proactively.

Life-best performances require life-best recovery.

Exhaustion is a feeling, not a state.

High-performance is about conditioning the mind to let the body go places previously deemed unsafe.

Back to Table of Contents

What I call “true green” training. Low stress across all markers: heart rate, lactate, substrate utilization and subjective perception => Zone 1.

“Athletic sustainability” requires being able to utilize fat for fuel. A topic not addressed in the book but one that directly impacts the stress of a given rate of energy expenditure.

Strength training, plyometrics and sprints. Done in a low stress manner. Beware => These can also be highly stressful sessions if performed in a sustained manner, with short rest periods.

As an elite, I’d change hemispheres with the seasons. I was exposed to “long days” for most of my calendar year.